Why Existentialism Can’t Escape the Imago Dei

January 7, 2026 — Kyle Tucker

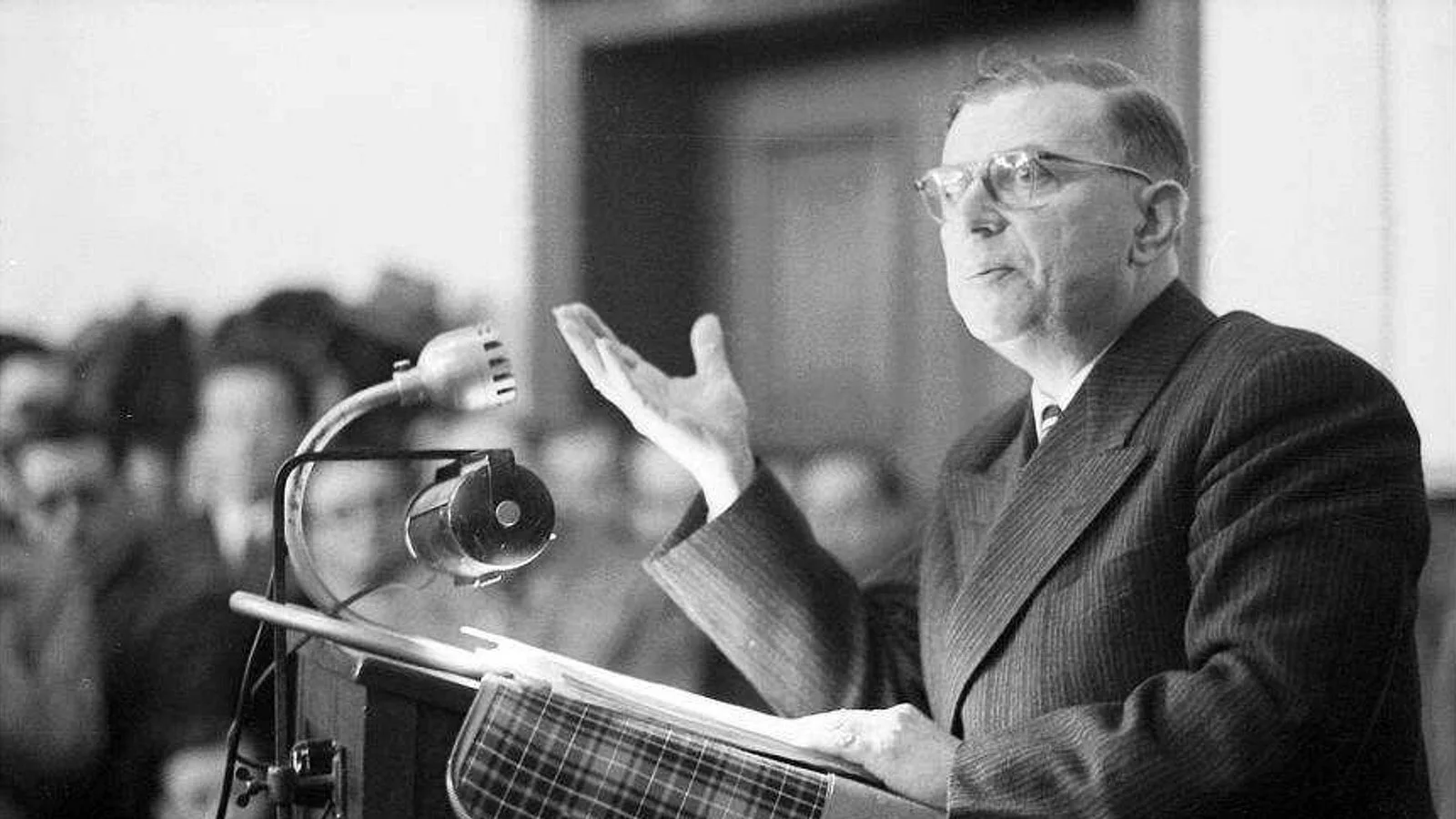

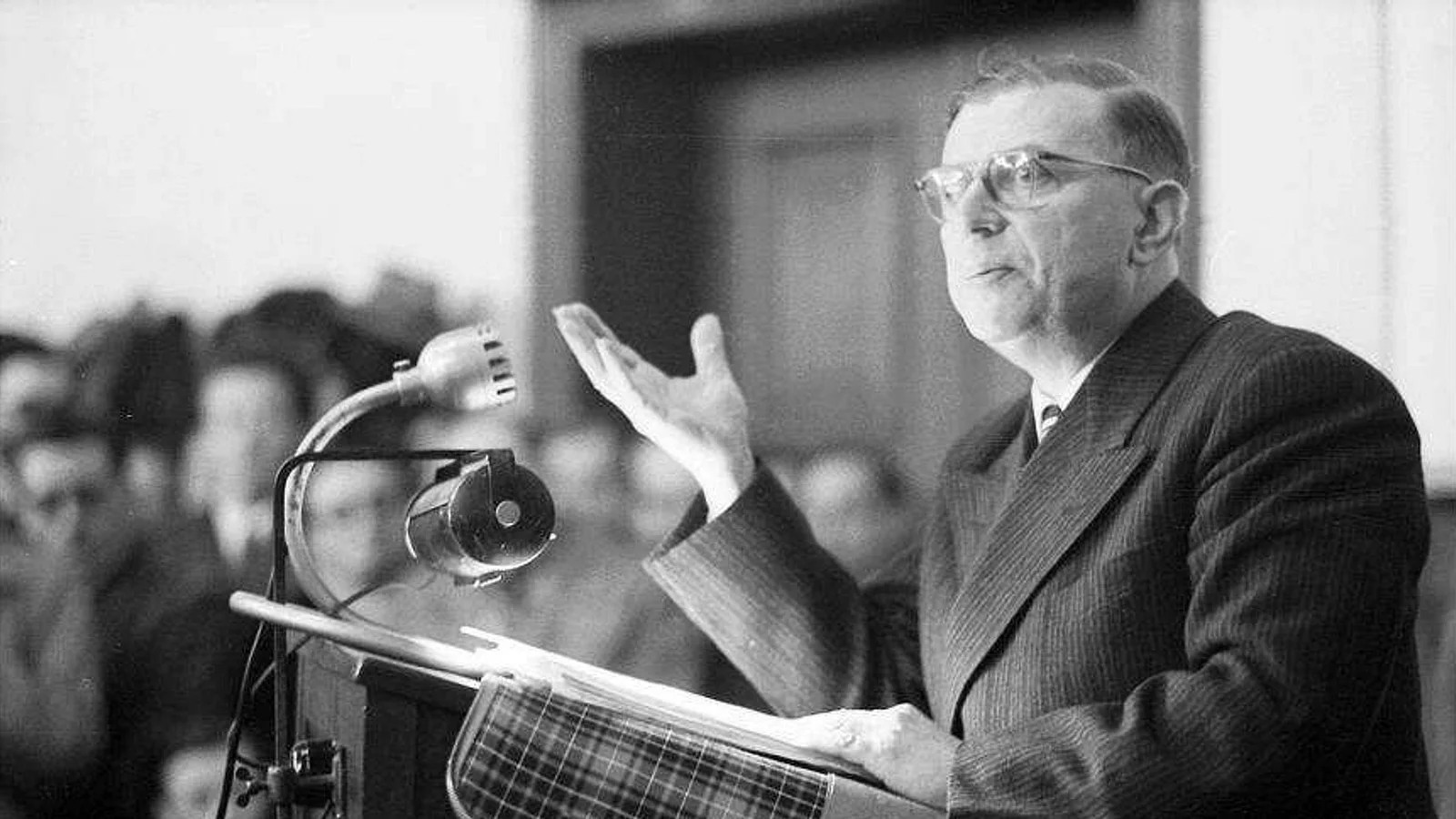

In 1946, Jean-Paul Sartre delivered a philosophical blow to Christian anthropology in his essay Existentialism is a Humanism. He wrote: “There is no human nature since there is no God to conceive of it.” You are, according to Sartre, a blank canvas in a world devoid of an ultimate standard of beauty and goodness. You must determine not only who you are but also what you are—no script, no design, and no objectivity. You are nothing more than the sum of your actions.

For some, this seemed liberating. Existence precedes essence, and therefore each of us is unfettered from the restraints of traditional morality. Sartre was at times right to correct the overly rigid and hypocritical Christian traditions of his day. But almost eighty years later, cracks have begun to show in Sartre’s vision. Not because it was overly ambitious, but because it was remarkably naive.

We live in the aftermath of Sartre’s existentialism. We believe ourselves to be free, and yet we are more lonely and anxious than ever. We long for a greater sense of dignity but have removed its foundation. We cry out for justice while denying its metaphysical existence. And in the absence of the divine, we have introduced the tyrant of self-actualization.

It is time to recover the transformative doctrine that Sartre rejected. You are made in the imago Dei.

The Foundation of Human Dignity

The biblical story begins with the undeniable dignity of humanity. God says: “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (Genesis 1:26). Human nature is not self-generated but humbly received. Further, the image not only defines what you do but who you are. You are a royal steward, a picture of the glory of God, a vicegerent of creation.

Unlike existentialism, the doctrine of the imago Dei is neither hopelessly optimistic nor overly cynical. The biblical story goes on to show that the image is shattered by sin (Genesis 3) and yet still retained from one generation to the next (Genesis 5:1–3). The divine likeness is disfigured but not destroyed. Every person—every class, race, gender, and age—still bears the stamp of the divine, no matter how distorted by sin.

The complexity of this biblical teaching accounts not only for the injustice we see around us but also the inherent value of the human person. We live in a time of moral outrage, and often for good reason. Senseless violence, unjust wars, corrupt politicians. Our hearts cry out against evil in the world.

Our indignation is warranted. But on what basis?

Westerners talk often about human rights. And yet we seem to have forgotten their origin. If there is no God, then how is human dignity anything more than a convenient mythology? Sartre was correct when he asserted that anything is permissible if God is dead. Or, to quote Yuval Noah Harari: “There are no gods in the universe, no nations, no money, no human rights, no laws, and no justice outside the common imagination of human beings.” In the absence of the divine, morality is nothing beyond mere preference.

But as thinkers like Tom Holland, Luc Ferry, and Samuel Moyn have shown, the very concept of human rights is deeply Christian. It did not come from Stoicism or Enlightenment philosophy. It emerged from the strange and remarkable Judeo-Christian claim that every human being bears the divine image. And because we are all image bearers, each of us is valuable and worthy of protection.

The Imago Dei as Common Ground

I pastor a church in Boston, one of America’s most educated, progressive, and secular cities. I have found that even the most irreligious person is haunted by the imago Dei.

Bostonians passionately defend the most vulnerable. We march for justice and defend the rights of the oppressed. And yet the dominant secular worldview of our city believes that we are evolved primates with no predetermined essence or morality. People intuitively know what they cannot explain.

A few years ago, a secular humanist chaplain at Harvard told me: “I don’t believe in God, but of course I still believe that I should be a good person.” In his view, self-interest can be utilized by democracy to encourage people to live ethically. While the basis of his ethical system was at odds with Christianity, he shared a deep longing to live a life of goodness and justice despite the meaninglessness and chaos of life.

Within this contradiction lies perhaps the greatest opportunity to connect modern people to Christianity.

The image of God provides a common basis for communication between Christians and non-Christians. There is a sense of the divine, an inherent knowledge of something greater, hidden within even the most ardent atheist. Even Sartre could not escape the feeling of abandonment, the awareness that he lacked something that ought to be present in his life.

As Tim Keller argued in Center Church, a robust understanding of the gospel, common grace, and the image of God provides not only a nuanced understanding of culture but also a basis of contextualization. Within every worldview, Christians can find areas of common ground and a basis for dialogue. This is not a denial of the radical antithesis between believers and unbelievers, but instead a recognition of the irremovable image etched into every human being.

In Sartre’s essay, there are remarkable areas of agreement that also provide a roadmap for engaging modern, secular Westerners with the gospel. Sartre affirms his own version of the golden rule, showing the continued longing in modernity for each of us to treat others the way we want to be treated. Further, Sartre recognizes that feeling is an insufficient foundation for morality, leaving the door open for Christians to critique emotivism as an ethical system.

And, most importantly, Sartre fiercely decries the kind of quietism that refuses to address the surrounding world. This is perhaps the most powerful connection that I have seen for urbanites who are exploring Christianity. Christianity offers an objective basis for condemning evil, a powerful vision for justice, and a hope that the world will one day be restored.

The Restored Image

Sartre is at his best when he identifies the feelings of anguish, abandonment, and despair that come with his existentialism. There are perhaps no three better words to describe the plight of people in the West today. Sartre inadvertently exposes a powerful longing that only the gospel can fulfill.

In this modern dilemma, the imago Dei offers a profound basis for hope.

When someone suffers from a chronic illness, or experiences gender dysphoria, or loathes their appearance, the image of God shows them that their body is not a prison but a work of art. Herman Bavinck famously wrote in his Reformed Dogmatics that the “whole human person is the image of the whole Deity.” In the entirety of every human being, God sees an infinitely valuable mirror of his image and delights in the beauty that he sees.

When someone feels that life is meaningless, the image of God reminds them that their life has purpose and value. Human beings were created to display God’s image to the world. God has made us queens and kings over creation, with the responsibility of stewarding creation. According to Genesis 2, we are like gardeners with the divinely mandated responsibility to take the raw resources of creation and turn them into something that displays the beauty of God. The divine image provides a meaning in life that is built into our very nature. Everything we do—every relationship, every vocation, every creative endeavor—is a way to display God’s beauty to the world around us.

Into modern anguish and despair, the gospel offers a better story. Jesus made the audacious claim that whoever had seen him had seen God. The biblical writers taught that Jesus is the very image of the invisible God, the radiance of his glory, the very imprint of his nature.

Christianity offers a far greater promise than existentialism. Sartre’s only hope was in the actions of humanity. But the message of Christianity is that the perfect image bearer was shattered on the cross so that the imago Dei could be mended in humanity. The call of the gospel is not striving for self-actualization but resting in divine restoration.

When Jesus returns, 1 John 3:2 says that “we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is.” The perfect renewal of the image of God will happen as every believer beholds God in Christ. In the presence of God, we will perfectly display God’s glory to the new creation.

Sartre was wrong. You bear an image that you did not create. Christianity teaches that you were made by a God who not only loves you but also promises to restore you. And that is very good news.